August 25, 2012

Britain desperately needs more homes

IN A city overflowing with people, the Heygate estate, near Elephant and Castle in south London, is an eerie place. Most of the flats lie empty, the windows and doors shuttered with metal plates. Concrete walkways, once intended as “streets in the sky”, extend uselessly into open air. Silent corridors are littered with sweet-wrappers, old newspapers and broken furniture.

The Heygate and its still-inhabited neighbour, the Aylesbury, have become symbols of the failures of post-war social housing. Built cheaply to replace crumbling Victorian slums in the 1960s and 1970s, the bright new buildings quickly deteriorated. Heating systems stopped working, communal gardens were badly maintained and the dark stairwells became infested with teenage gangs and drug dealing. Like many similar estates, the Heygate and the Aylesbury are scheduled for demolition and redevelopment.

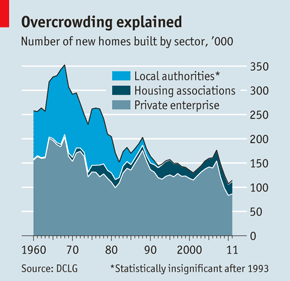

Although the 1960s and 1970s produced bad homes, they did at least produce homes. Stopped by rules introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s government, social-housing starts collapsed after the 1970s, when they were running at up to 118,000 a year (see chart). Private house-building has never made up the difference. Demand for all sorts of housing is growing—the government estimates that 232,000 households are created each year. Private-sector rents rose by 4.3% last year, and 1.8m families are waiting for social housing, a 77% increase on ten years ago.

Ministers know this, and recession presents an opportunity. In the 1930s Britain weathered the great depression better than many countries thanks partly to unprecedented house-building, much of it by local councils, says Nicholas Crafts of the University of Warwick. The government now wants to repeat the trick. David Cameron, the prime minister, speaks of “getting Britain building”; his chancellor, George Osborne, has a habit of being photographed near construction sites.

But there is no more state money for new social housing: the capital grant was cut by 63% in 2010. Instead, the government wants private investors such as pension funds to finance building social homes. To achieve this, social landlords (mostly independent housing associations these days, rather than local authorities) are now allowed to charge an “affordable rent” of up to 80% of local market rents for new tenants—much higher than the “social rents” previously charged. This should attract enough private investment to build 170,000 “affordable” homes by 2015, says Grant Shapps, the housing minister.

Unfortunately, Mr Shapps may miss even his modest target. While charging tenants more may increase revenues, most social tenants are on housing benefit now, and their rent is paid directly to landlords by the state. This benefit has been cut and capped, and from next year it will be rolled into a new universal credit, leaving tenants to pay their own rent along with grocery bills, clothing for children and so forth. Arrears may well increase. That prospect makes it harder to tap institutional investors for long-term development funds. So do threats of more welfare cuts to come.

Construction, so far, is down. Building began on 15,700 affordable homes in 2011, compared with 49,000 in 2010 under a scheme started by the previous Labour government. Things should improve next year, says Christine Whitehead of the London School of Economics, as new contracts have been signed, but it is far from certain how many homes will be built.

Ministers are said to be considering the possibility of guaranteeing housing associations’ borrowing to build. Others have bolder ideas. Policy Exchange, a think-tank, caused a furore on August 20th when it suggested selling council homes worth more than the regional median as they become vacant and using the £4.5 billion a year this might raise to pay for extra social homes elsewhere (see Bagehot). Mr Shapps calls the idea “blindingly obvious”.

A report for the government by Sir Adrian Montague, a financier, published as The Economist went to press, suggested loosening restrictions on commercial building of rented homes. Mr Shapps is keen on that, too. Many projects are held up by negotiations between councils and developers over how many “affordable” homes are included. Sir Adrian wants conditions relaxed for builders who rent their properties instead of selling them. That is controversial, but may increase supply. At the Heygate estate, most of the new flats will be sold privately. But if cheaper rents emerge from a larger housing stock, that will help social tenants too.

Source: The Economist

Leave a Reply